The Oldest Recorded Case of Spinal Cord Injury

- Diksha Joshi

- 1 day ago

- 4 min read

Have you ever wondered when the first recorded case of spinal cord injury occurred? Or how humans understood the body long before X-rays, CT scans, or anatomy textbooks?

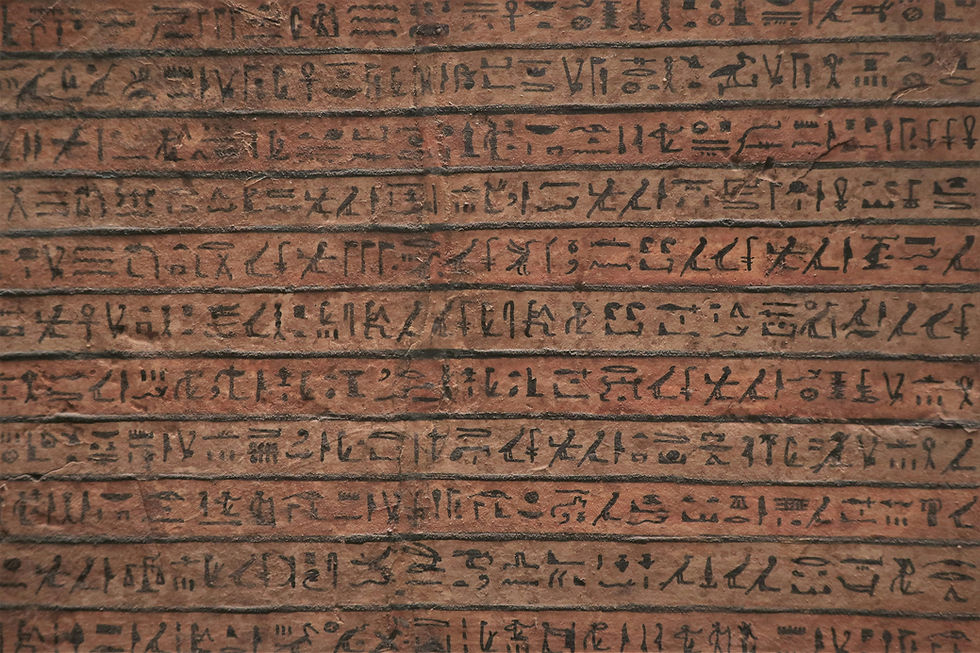

Some of our earliest insights into spinal cord injury come from a document that is more than 3,500 years old; a fragile medical scroll that survived centuries buried in an Egyptian tomb.

The present blog explores the earliest recorded case of spinal cord injury in the Egyptian papyrus, and how the 3500 year old knowledge of spinal cord injury compares to our modern understanding of it.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus

Dating back to the seventeenth century BCE, the Edwin Smith Papyrus is the oldest known surviving trauma text in history. Unlike other ancient medical writings steeped in mysticism, this papyrus is scientific in its approach. It presents 48 clinical cases, six of which focus on injuries to the spine, and describes signs and symptoms with an accuracy that still feels familiar to modern clinicians.

For over 3,000 years, the papyrus lay hidden in Thebes, Egypt, until it was acquired by an antiquities dealer named Edwin Smith in 1862. Although Smith recognized its importance, he was never able to translate it. After his death, the scroll was donated to the New York Historical Society, where it eventually caught the attention of renowned Egyptologist James Henry Breasted.

In 1920, Breasted undertook the enormous task of translation. After years of study, he published a two-volume English edition in 1930, complete with medical commentary prepared by physician Arno Luckhardt. Since then, scholars and clinicians have continued to revisit and reinterpret the text, refining our understanding of its medical insights. Most recently, researchers have worked toward a “medically based translation” that aligns ancient terminology with modern clinical concepts.

How Ancient Physicians Thought About Injury

What makes the Edwin Smith Papyrus so remarkable is its structured clinical reasoning. Each case follows a familiar format that physicians can identity and continue to use in modern medicine. The following is the manner and order in which medical information is organized in the text:

Introductory heading

Significant symptoms

Diagnosis

Recommended treatment (if the condition was deemed treatable)

And often, an Explanation section clarifying unfamiliar terms

Many of the injuries described are thought to have occurred during battle or construction work, reflecting the risks of daily life in ancient Egypt.

One case, for example, attributes a spinal injury directly to mechanism:

“It is his fall head-downward which caused a vertebra to crush into its counterpart.”

Another case describes a patient with a lumbar spine injury being asked to extend and contract their legs while lying supine. Immediate leg contraction due to pain was used as a diagnostic clue, suggesting an early form of neurological and musculoskeletal examination.

The First Descriptions of Spinal Cord Injury

Two cases in the papyrus (Cases 31 and 33) are now understood to describe true spinal cord injury. Interestingly, these cases do not focus on stiffness or movement of the neck or spine. Instead, all recorded symptoms relate directly to spinal cord dysfunction.

One phrase appears in both cases:

“Unawareness of both the arms and the legs.”

This wording is striking in its clinical observation for this time period, recognizing that both motor and sensory function were completely absent.

Even more remarkable, the papyrus contains the first known descriptions of autonomic dysfunction associated with spinal cord injury. Symptoms such as priapism, urinary incontinence, and abdominal distention are carefully documented, highlighting an early understanding of how spinal cord injury affects far more than movement alone.

Prognosis Over Treatment

While the papyrus categorizes spinal column and spinal cord injuries with surprising clarity, treatment options 3,500 years ago were limited. Many spinal cord injuries were labeled as “an ailment not to be treated”, because while it now clear the Egyptians had an understanding of the injury, there was no corresponding treatment available.

Given the devastating outcomes of spinal cord injury at the time, prognosis played a central role in decision-making. Most patients likely died shortly after injury, often due to complications we still recognize today including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and consequences of autonomic dysfunction. In that context, detailed descriptions of vertebral fractures may have seemed less important than documenting symptoms that predicted survival.

What is different and what remains the same

Centuries later, breakthroughs like X-rays (1895) and CT imaging (1971) transformed how spinal injuries are diagnosed. Imaging replaced history-taking and physical examination as the gold standard for assessing spinal column damage.

Simultaneously, more than 3,500 years after the Edwin Smith Papyrus first categorized spinal injuries, we still lack a single, globally endorsed, fully reliable spinal injury classification system. Despite extraordinary technological advances, some of the fundamental challenges remain unresolved.

A medical, historical marvel

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a testament and reminder that while we have come a long way as post-modern humans, at our core, we were have always been incisive, remarkably intelligent and resilient in our search for knowledge and understanding.

Long before modern neuroscience, ancient physicians recognized paralysis, sensory loss, and autonomic dysfunction without any knowledge of physiology and modern medicine as we know it today.

Reference